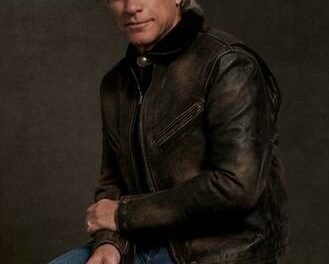

Harold W. Miller, one of America’s best postmodernist African American sculptors with one of his latest masterpieces.

By Danny R. Johnson

“Who can be born black and not sing the wonder of it – the joy, the challenge. And to come together in a coming togetherness vibrating with the fires of pure knowing and reeling with power, ringing with the sound above, sound above, sound to explode in the majesty of our oneness, our coming together in a coming together. Who can be born black and not exult!”

Mari Evans, Author and Poet

JACKSON, MS – Upon first seeing the works of sculptor Harold W. Miller, the majesties of his African American male and female statues appeared so real and enlightening: then there is the sweetness and the dignified postures of the African American women clay statues which leaps out at you like a leopard going after its prey. In some of the statues there is an acrid edge, like a thousand burned scars which no one but those who have experienced pain and suffering can relate. Then you’re struck by the attention to details right down to the eyes, mouth and face as a whole. When you complete the observation of these extraordinary pieces of art, you can’t but marvel at the creative genius that is Harold W. Miller.

In his smoothly modeled clay, wood and stone sculptures, and vigorous woodcuts, Miller drew on his experience as an African American man who had come of age in the late 1960s and early 1970s at a time of widespread de-segregation who had felt its sting growing up in Vicksburg, Mississippi, located 45 miles east of the capital, Jackson. But his art has other influences besides the African Diaspora — it includes the African American church, sharecroppers, the African American family’s journey in America, and the triumphs and struggles of freedom.

“The experience of having lived in a home that rested between a church and a juke joint inspired me to give relevance to a bygone era,” stated Miller. Miller’s works of art is demonstrated by the spiritual nature of his church lady figurines that appear to sing praises as they pray, or churn milk and the reliefs that honor the blues.

His best-known works depict African American women as strong, maternal figures. In one original sculpture, Emma (2013), a young African American woman in her Sunday’s best is captured and praying. In another piece, Marla (2013), a proud and royal Nubian queen is standing tall in her magnificent African adornment in a gesture of vitality and confidence.

In his Brandon, MS studio which is located 6 miles west of Jackson, the 57 year-old Miller is a proud Black man — standing at “5-10,” with a round face sprinkled with perfectly adorned freckles. He walks with a slight strut like a self-assured hipster with a sense of purpose. When he speaks you are drawn to every word because he speaks fast but with perfect articulation and in a mid-range tone.

“Art to me has to connect with humanity and absence of that it serves no meaningful purpose,” Miller stated in measured and serious tone.

“An artist never creates anything from their imagination one of my master arts instructors once told me. He said that all art is created from the depths of despair of one’s soul, personal reflections and experiences,” emphasized Miller.

Miller is a self-taught sculptor whose fascination with clay began at the age of six as he hulled and fashioned animals with clay from the embankment of a bayou behind his boyhood family home in Vicksburg. After attending Hinds Community College and Jackson State University’s pottery classes and workshops, Miller began to grasp the creative aspects of watching people and transposed and immersed those life experiences into the world of life-like creations captured in clay.

Miller is known for uniquely creating brilliantly colored wind figures whose cloaks show movement in clay as they appear to withstand winds that may challenge one’s dreams. He has created various sculptures that include his knowledge of pottery such as three-faced vases and even the bottoms of some of his wind figures. Additionally, he creates life-sized dolls, bust, frames for his reliefs, tables to exhibit his work on and awards. Miller’s work is represented in the permanent collections of the Mississippi Museum of Art, Smith Robinson Museum of Art and Hinds Junior College.

In the 35 years since his first sculptor creation, Miller has created dozens upon dozens of art work for clients all over the world.

“I have clients who come to me every year commissioning me to create an original piece for them,” Miller excitedly explained. “It’s gratifying to know that somewhere in the world a piece of my art is representing my soul and the souls of Black folks and their experience in America.”

As artists and audiences grew more conversant in the diverse ways that one could express Black culture, the 1970s and 1980s ushered in a variety of artists such as Miller and artworks all comfortably operating under the rubric of Afro-American art. From the photo-realism of painter Barkley L. Hendricks and “neo-mannerist” stylizations of painter Ernie Barnes to the cloth-and-canvas accretions of mixed-media artist Benny Andrews and altar-like installations of sculptor Beyte Saar, African American art could no longer be contained in neat, stylistic categories. The important exhibitions of past and present African American art organized by curators David C. Driskell and Edmund B. Gaither and the definitive histories and art publications of Elsa Honig Fine, Samella Lewis, and Ruth Waddy helped educate the experts and uninformed public alike on all that might constitute an African American art.

Harold W. Miller Represents the Best of Post-Modernism African American Art

Harold W. Miller comes from a long list of African American artists/sculptors who represent the postmodern era of Black art. By the mid-to late 1980s earlier definitions of African American art would be supplanted by the postmodernist tenets of cultural relativity, art-as-performance, critical inquiries of art and society through one’s work, and interrogations of identity, geography, and history. Several artistic precursors to this new generation had already begun to exhibit these more provocative, postmodernist characteristics in their work. For example, by 1975 when Miller was just about to launch his professional career, artist David Hammons was already creating sculptures from Black cultural detritus (hair, food, artifacts, etc.) that ironically commented on Black identity. Around the same time Robert Colescott was making outlandish, cartoon-like paintings that poked fun at the art establishment, cultural conservatives, and ethnocentrism. In contrast, conceptual artist Adrian Piper countered the reigning avant-garde of her day with performances that placed racism at the center of art matters. Also at this time artist Houston Conwill wrestled with the notion of African American space, initially through site-specific earthworks and, later, through culturally informed diagrams and signs.

These pioneers of an African American visual postmodernism helped put into motion a different set of visual criteria in contemporary art: models that, in turn, have engendered an innovative group of artists such as Miller. This inventive group includes sculptors Alison Saar and Renée Stout and photographers Albert Chong and Lyle Ashton Harris, who explore concepts of object hood and fetishism; visual artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Glenn Ligon, and Lorna Simpson, for whom issues of gender and language are central in art; photographers Dawoud Bey, Renee Cox, and Lorraine O’Grady and painters Kerry James Marshall and Howardena Pindell, each of whom presents the Black body as a site of theoretical warfare, social research, and desire; and conceptualists like Gary Simmons, Kara Walker, and Fred Wilson who, through installation art, have problematized American history and the psychology of racism so that display and spectatorship can no longer be viewed as purely innocent acts.

In his own words, Miller is more concerned with the social dimension of his art than its novelty or originality. As he told me at the conclusion of our interview, “I have always wanted my art to service my people — to reflect us, to relate to us, to stimulate us, to make us aware of our potential.”

Harold W. Miller Handcrafted Sculptures of Brandon, MS can be found on FACEBOOK.

Danny R. Johnson is San Diego County News’ Arts/Entertainment News Editor.